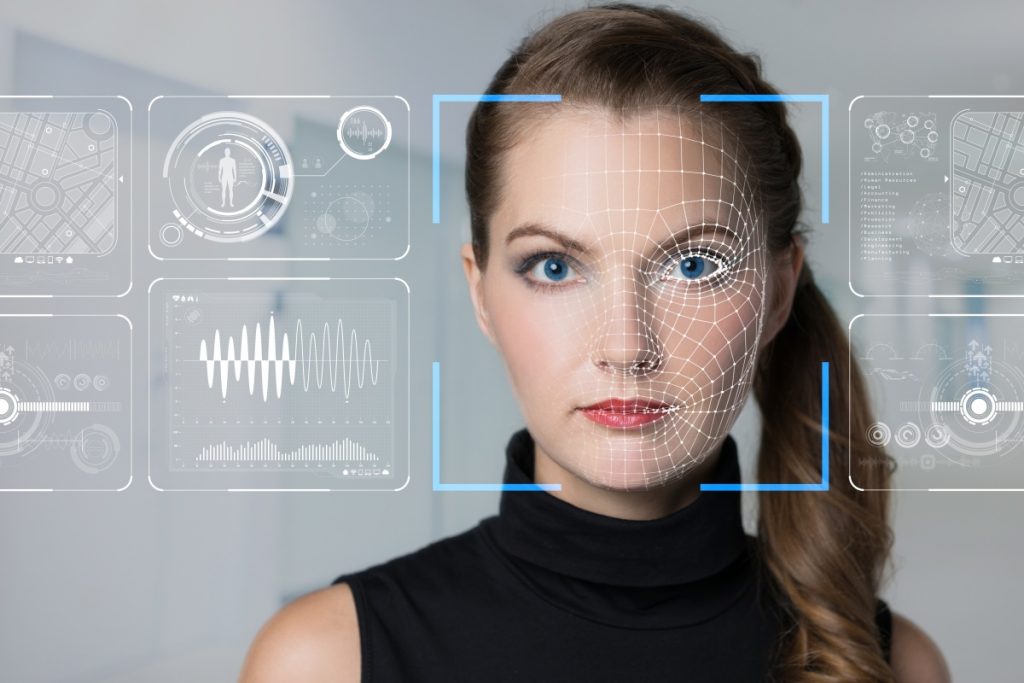

In the security room of the River Spirit Casino in Tulsa, Oklahoma, thousands of faces are shown every day on rows of screens. Each one is checked against the casino’s list of banned people, which could be a cheater, a known criminal, or an ex-employee who is upset and wants to cause trouble.

Face recognition technology made by the Israeli surveillance company Oosto is used in the casino’s security system. The controversial company, which used to be called AnyVision, made headlines in 2019 when it gave the Israeli government technology that it used to watch the border with the West Bank. Now, though, the company has changed its name and is focusing more on private businesses, like casinos.

In July, a Forbes video producer was watching the surveillance hub in action when a blue box appeared around the head of a woman who was wearing a mask. It turned green after that. A green box in this software is a red flag. Even though she was hiding her face, Oosto’s facial recognition made it clear that she was not welcome.

“She’s definitely trying to hide her identity because we got a really high score,” said Travis Thompson, director of compliance and surveillance for Muscogee Nation Gaming Enterprises, pointing at a screen running Oosto’s software. He said that when the software flags a person, the casino checks the person’s identity in person.

If they are on the banned list, staff will give them a form reminding them that they are not welcome and that their faces are in the casino’s facial recognition database before showing them the door.

It’s the kind of surveillance that’s happening on private property and in public spaces all over the United States now that this powerful technology isn’t just in the hands of the police and the federal government, but is also sold to private businesses like casinos and stores.

Privacy activists are worried about the privatization of tools that were once mostly used by intelligence and law enforcement agencies. Companies see this as a way to improve their physical security.

“Selling facial recognition technology to private companies can actually make it more likely that police will abuse it,” says Jake Wiener, a lawyer at the Electronic Privacy Information Center who works on domestic surveillance (EPIC). “As a starting point, facial recognition hurts privacy.” “The more it’s used, the easier it is to track people in both public and private places.”

On the other hand, Oosto wants to be the top company in this market of private entities that want to improve their surveillance, both in the U.S. and in Europe. Since its start in 2015, the company has raised $380 million from investors like SoftBank and Qualcomm Ventures. It was first called AnyVision, but because of its customers, it got into trouble.

In 2019, the Israeli news site Haaretz said that the surveillance company gave its tools to the Israeli military so they could identify Palestinians at the border with the West Bank. After this, Microsoft’s investment arm M12 sold its shares in the company.

Since those reports, Oosto has not only changed its brand, but it has also turned its attention more to the private sector and is now serving a large area. At the moment, its technology keeps an eye on football fans going to see the New Orleans Saints, tourists at the Taj Mahal in India, visitors to Tel Aviv’s private Raphael Hospital, and people watching horse races at the Australian Turf Club in Sydney.

Casinos are a big part of its business outside of the government. Oosto says that it works with some of the biggest casinos on the Las Vegas Strip, but it won’t say who those casinos are.

It also helps the private casino Les Ambassadeurs in London’s upscale Mayfair district recognize people by their faces. There, Oosto’s technology isn’t just used to find bad guys; it’s also used to find VIP guests and serve them.

But the owners of River Spirit Casino decided not to use it to find VIPs because they thought it would be unethical. “We want it to be a place where people feel comfortable, so we don’t want them to feel like Big Brother is always watching. “But our system is not here for that,” says Thompson.

Instead, he says that the casino decided to use facial recognition because security staff on the casino floor were “struggling to recognize faces just by looking at them.”

“It was up to our security guards and floor staff to go out and remember who these bad customers and bad actors were, and to try to see that in a sea of people every day,” says Thompson.

He says that the casino and the police worked together and that the facial recognition system was a big part of putting people in jail. He wouldn’t talk about specific cases, but he did say that people have used surveillance devices to cheat at poker and add money to bets without anyone knowing.

Even though the casino says it will only use the technology to protect its most innocent customers, whose faces will not be stored on its systems, critics of facial recognition say that this isn’t enough to protect people’s privacy. Freedom of information requests and other forms of oversight applies to police and government agencies, but not to private entities, even though they can put anyone on a watch list and help put people in jail.

“At the very least,” says Epic’s Wiener, “Oosto should keep records of searches run and decisions made.” “If a person’s Oosto ID keeps them from getting into an event or, worse, gets them arrested, that person should be able to find out how they were identified.”

Aside from the creepiness of scanning the faces of hundreds of thousands of people every day, the technology has a history of not being able to find people who are not white. False positives have previously resulted in the wrong arrests of black men. Earlier this year, senators asked federal agencies to stop using the technology because it “poses unique threats to black communities, other communities of color, and immigrant communities.”

Facial recognition is not being used anywhere in the U.S. because of the backlash against it. In a recent case, the ACLU of Illinois was able to get a company called Clearview AI to stop selling in the state or to private American companies.

The company had already said it wouldn’t sell to non-government organizations in the U.S. In Vermont and Portland, Oregon, police and private organizations are not allowed to use facial recognition. Some bans will end in the next few months.

Face recognition and biometric scanners can’t be used in body-worn cameras in California right now, but only until January of next year. Virginia had banned police from using facial recognition, but that ban was lifted in July. However, the state’s new law only allows products that “have an accuracy score of at least 98% across all demographic groups.”

Dean Nicolls, who is in charge of marketing at Oosto, says that major providers have mostly solved the problem of bias. “If you train your AI on a bunch of middle-aged white guys, it will be really good at picking up and detecting middle-aged white guys, but it might not do so well with African American women.” Most of these biases have been removed. If you look at the top players in facial recognition, you’ll see that they have almost no bias when it comes to age or race.

The company refused to give any information about how well its technology did in bias tests. A DHS study that started last year found that the best algorithms can find people with over 95% accuracy, no matter what color their skin is. However, overall, the technology was still better at finding white men than any other group.

Nicolls says, though, that Oosto doesn’t just use facial recognition. It is planning to move into the behavior recognition field, which is just as controversial. Even though there is more and more evidence that software can recognize a face with well over 90% accuracy, it has not yet been proven that code can tell if a person is acting dangerously or what they are thinking by looking at how they move. When Forbes wrote about companies that could read and predict emotions, Meredith Whittaker, who helped start the AI Now research institute, said that the technology had “no sound scientific consensus.”

Forbes reported last year that Oosto had a patent to put its facial recognition technology on drones, which would take surveillance to the sky. It hasn’t used that technology yet, though.

If Oosto keeps trying to push the limits of what surveillance technology can do, it will run into even more technical and moral problems. Even though former Attorney General Eric Holder found that Microsoft’s investment in the company didn’t break any of the tech giant’s ethical rules, the company’s decision to end its relationship with the company in 2020 showed the risks of helping to spread the technology. “For Microsoft, the audit process showed how hard it is to be a minority investor in a company that sells sensitive technology,” the company wrote before saying it would no longer be a minority investor in facial recognition businesses.