SCARF (swept-coded aperture real-time femtophotography), a research-grade camera, could advance micro-event research, which is too fast for the most expensive scientific sensors. SCARF (swept-coded aperture real-time femtophotography), a research-grade camera, could advance micro-event research, which is too fast for the most expensive scientific sensors.

Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS) professor Jinyang Liang of Canada was in charge of the research team. His work in ultrafast photography, which he expanded upon six years ago, has garnered international renown. Science Daily was the first to report on the latest study, which was published in Nature and summarized in a news statement by INRS.

A new perspective on ultrafast cameras was the focus of Professor Liang and colleagues’ research. These systems usually work sequentially, taking pictures one by one and then piecing them together to see moving objects. There are drawbacks to the method, though. This method is “not applicable” to studying phenomena like optical chaos, shock-wave interaction with live cells, and femtosecond laser ablation, according to Liang.

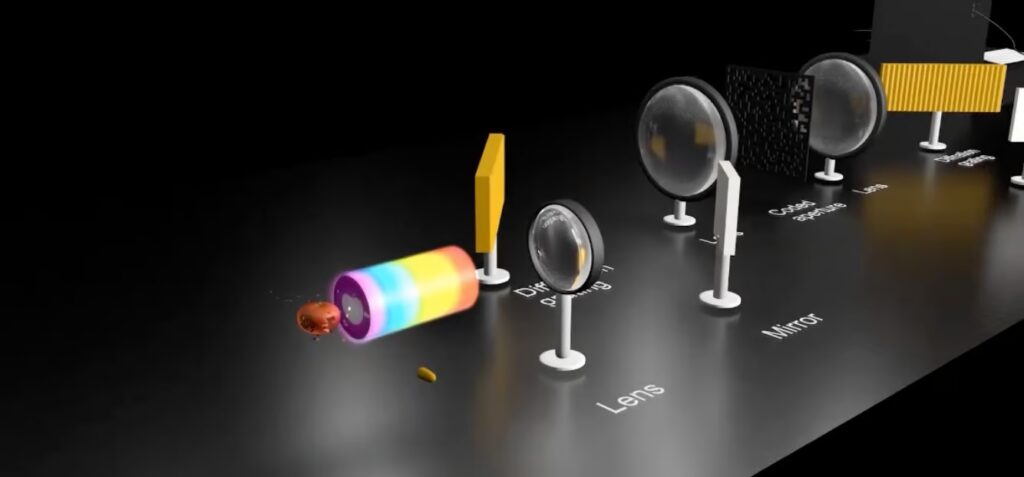

Using Liang’s earlier work as a foundation, the new camera challenges the conventional wisdom around ultrafast cameras. “SCARF overcomes these challenges,” stated Julie Robert, a communication officer for INRS. Its imaging mode allows for the shearing-free, rapid sweeping of a static-coded aperture. This allows charge-coupled device (CCD) cameras to capture full-sequence encoding at rates of up to 156.3 THz per pixel. These results can be achieved in one shot using reflection or transmission modes with customizable frame rates and spatial scales.

Read More: A Sims Movie Starring Margot Robbie is in Production

Ultrafast Computational Imaging

A very simplistic explanation would be that the camera lets light into its sensor at slightly varied times, using a computational imaging modality, to gather spatial information. The camera can capture “chirped” laser pulses at 156.3 trillion times per second since it does not need to interpret spatial data. A computer algorithm can decipher the time-staggered inputs and interpret the raw data from the photos, resulting in a comprehensive picture from each of the billions of frames.

Using “off-the-shelf and passive optical components,” as described in the report, it accomplished this remarkable feat. In comparison to current methods, the team claims that SCARF is inexpensive, uses little power, and produces high-quality measurements.

The team is already collaborating with Axis Photonique and Few-Cycle to create commercial versions, perhaps for their academic or scientific institution colleagues, even if SCARF is more focused on research than consumers.